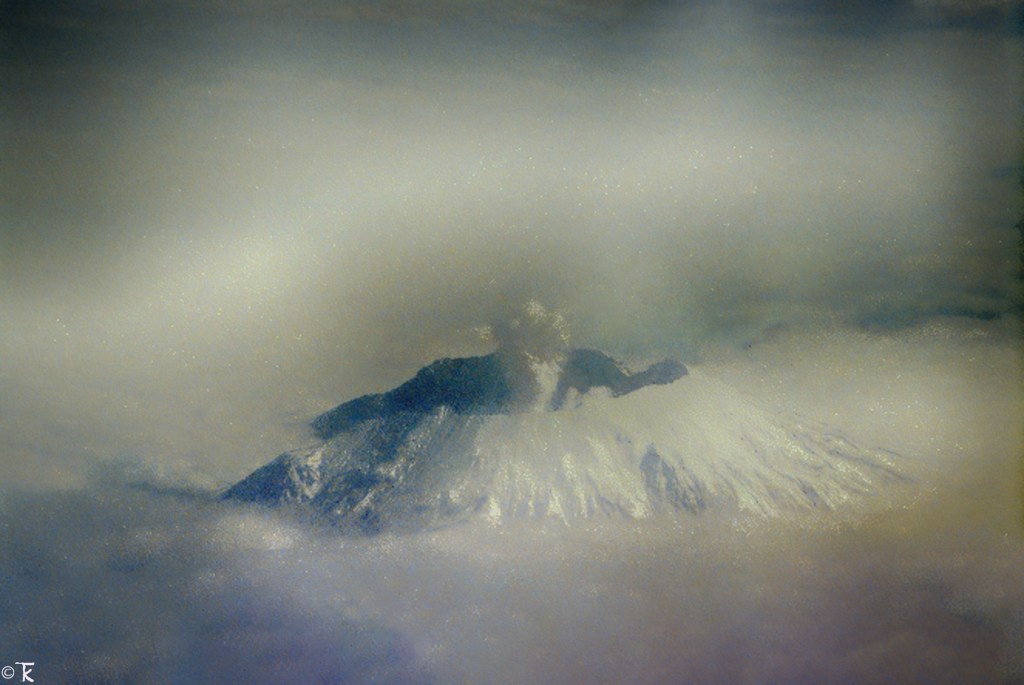

Mt. St Helens was still smoldering 17 months after it’s eruption when I flew over it on my way to Anchorage in the fall of 1981. The fractured peak, its top blown off in a cataclysmic display of force, appeared dark and foreboding as we flew by, a terrible reminder that we live in a world where nature dictates the terms of our occupancy on a basis that, when it comes right down to it, is non-negotiable. We defy it at our peril.

Mount St. Helens ©1981-Tim Konrad Photo

Possessed, as we are, by relatively short life-spans, our imaginations are limited by our human perspectives. We tend to believe that volcanic eruptions, massive earthquakes and the like occur too seldom to be of much concern. The geologic time-scale on which such events take place is too abstract for us to wrap our minds around: To make sense of them we construct narratives designed to reduce these phenomena to human scale. We tell ourselves “There’s no need to worry. That volcano hasn’t erupted in over eight-hundred years,” or “the last great earthquake in this area occurred in 1791” and so on.

Framing our understanding of the natural world in this manner makes life a little less foreboding much the same way the little fictions we tell ourselves in our daily lives help us deal with the uncertainties of daily living. If, as in the case of geophysical events, the scale of things exceeds our ability to grasp them, we bring them down to a size that better accommodates our relatively limited capabilities. Doing so also allows people to maintain beliefs that, in instances like that of Harry Truman, the man who

refused to leave his mountain paradise on the slopes of Mount St. Helens, despite having been warned repeatedly he should do so, have proved to be dead wrong.

When people eschew reality in favor of their personal fictions, disaster is certain to follow. This is true regardless of the nature of the fiction or the numbers of people ascribing to it. And this truth is not limited solely to the natural world.

The same may be said regarding the fictions currently being told by the Republican Party in its desperate attempt to retain power and control amid a political landscape in which its ideas are no longer relevant to the needs of the people it claims to serve.

***

As noted earlier, eccentricity was woven into the fabric of the mindset of Alaskan society, or at least into the parts of it I encountered in my travels there. The sign house was one manifestation of that phenomenon, but others could be encountered in the most unexpected of places. While riding along in the tundra with Dave over one of Nome’s few roads one afternoon, we came upon a partially dismembered child’s doll leaning up against the gnarled root base of an upended tree. The object, glistening in the late afternoon sun, possessed an aura bordering on the macabre, perched as it was between impropriety and the chaos of dissolution.

Tundra Doll ©1981-Tim Konrad Photo

Mysterious and unsettling, the scene could have equally served as a prop in a Twilight Zone episode or the tundra variant of a Rorschach Test. Either way, I thought to myself, it attested to mans’ ingenuity in combatting the boredom associated with the long nights of winter bordering the Arctic Circle.

Tim Konrad

(To be continued . . )

Leave a comment