Paradoxically, cutting firewood was a popular activity in Nome, even though, thanks to the permafrost, there were no trees growing anywhere nearby. The area’s beaches, however, were littered with prodigious quantities of driftwood sourced from trees growing along the watershed of the mighty Yukon River. The river’s force carried the collateral damage done by decades of downpours downstream, where it was deposited into the sea as the river’s waters intermixed with the salty brine of Norton Sound. From there, the ocean currents swept the detritus directly across the sound, depositing it along the swaths of shore-land surrounding Nome.

Driftwood lining beach ©1981-Tim Konrad Photo

Many locals heated their homes with driftwood they harvested from the beaches, Dave among them, using chain saws to cut big sections of logs into pieces small enough to accommodate their wood stoves. The work was hard on the sawblades, as the wood was sometimes impacted by spikes, nails and other pieces of metal that would dull or otherwise damage them. The notion of cutting firewood where none grew struck me as ironic and only added to my excitement at finding myself embedded in this land of exotic contradictions.

***

Terry was working as a public health nurse during my visit with her and Dave. Her work took her around to many of the villages and settlements scattered about the Seward Peninsula. As a result, she’d been able to make the acquaintance of many of the area’s indigenous residents.

One day she took me to meet some Inupiaq families at a fishing camp located near a beach a few miles east of Nome. (With a south-facing coastline, I always had to work out directions in my head while I was there. Being accustomed to the sun setting in the west, where I’d always lived, my brain told me that anything located ‘down coast,’ should have been south, not east).

Looking west from east of Nome ©1981-Tim Konrad Photo

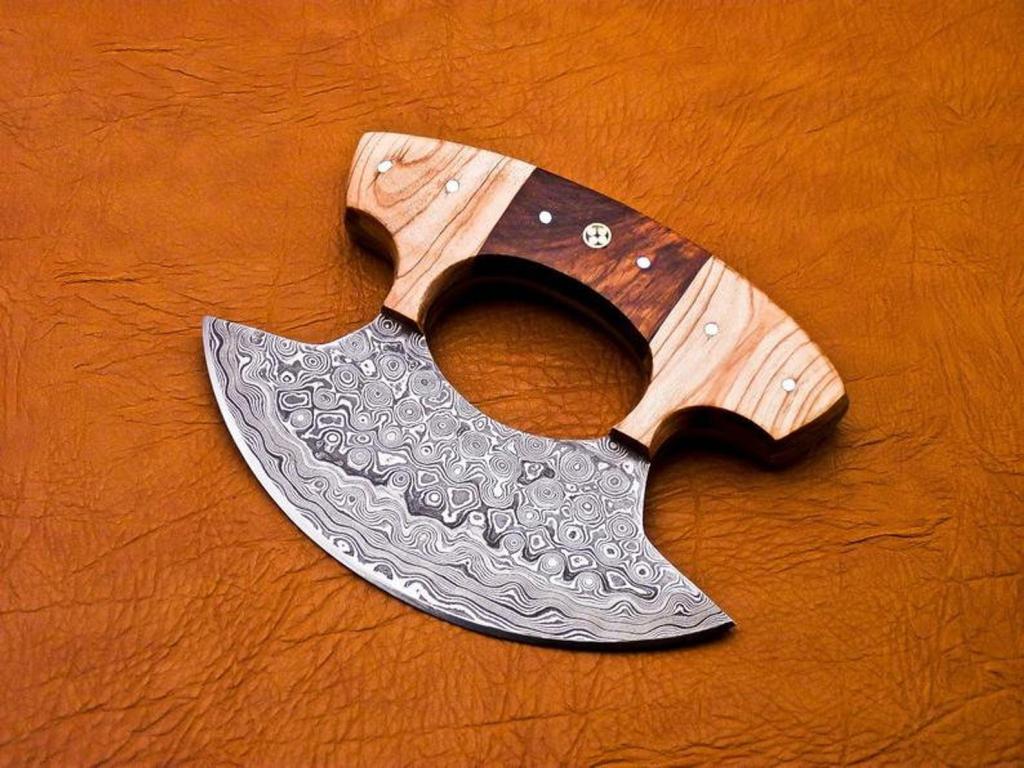

When we pulled up to the camp, a handful of people could be seen busily engaged processing newly hunted seal carcasses. A couple of women were skinning one of the animals while several of the men were busy cutting large slabs of blubber from the carcass of another. For this purpose, a specially-designed, round-bladed hand knife, known as an ‘ulu,’ was used.

A decorative ulu. The ones I saw were much less fancy. Photo: Etsy.com

Similar to a nut chopper, the ulu was deployed in a pushing motion to separate the blubber into manageable-sized portions. The blubber, called ‘muktuk’ in the local language, was an integral part of the Inupiaq diet. Packed with nutrients, muktuk, was a source of energy and was also said to help those who ate it to keep warm. Some say it tasted like fried eggs, while others compared it to fresh coconut. Advised by my friends that muktuk was not for the faint of heart, I chose to forego the delicacy.

Muktuk was also available for purchase at the local grocery/department store, where it sat in a freezer case alongside numerous species of fish and other frozen goods. Unlike similar places of business back home, this store also featured large-caliber hunting rifles, bullet-reloading supplies, extreme cold weather equipment, a dizzying array of fishing gear and steel-jawed bear traps in graduated sizes.

Cutting up seal blubber was not without its risks, Terry told me. In addition to the obvious danger the slip of a knife entailed, the blubber contained a particular type of microorganism that, if allowed to enter one’s body through cuts and scratches, often resulted in an infection that was exceedingly difficult to treat. Ever the optimist, Terry was quick to note that, on the plus side, Nome’s forbidding winter temperatures were inhospitable to the rhinoviruses and influenzas that were the bane of those residing in more temperate zones.

After visiting the fishing camp, Terry drove us a few miles farther ‘east’ to an area she said had once been home to people hundreds to thousands of years ago. The place at first looked much the same as everywhere else in the surrounding area, nothing but sand, beach grass and low-growing shrubs.

A closer look, however, revealed signs of earlier habitation scattered about, namely trade beads, likely acquired from Russian traders who began infiltrating the region in the mid-1700s. The beads were very similar to ones I’d found in California poking about old MiWok sites—small in diameter and colored a bright shade of red-ochre. The objects appeared unremarkable until I picked one up, held it to the light and was able to peer through it. Looking at it through its side, where the hole went through, revealed the bead was actually made of translucent green glass that had been coated with ochre on its outer edge.

As I pondered the wonder of that discovery, I found myself also wondering what those Russian traders had obtained in exchange for their shiny trinkets those several centuries ago and if, like the Dutch had done when they’d ‘purchased’ Manhattan from the Lenape for a miserly $24 worth of trinkets, the Russians had taken unfair advantage of the Eskimos.

Tim Konrad

(To be continued . . )

Leave a comment