By

Tim Konrad

A collection of short essays on my recollections of growing up in the Sierra foothills in the 1950s.

Introduction

The threads of the personal and the interpersonal are woven together throughout the Universe.

***

While mystics may speak of living in the eternal present moment, or the “now,” for the rest of us, according to Hank Steuver, “there is only this sort of present-tense past that we all live in, full of remakes and revivals and constant nostalgia.” (Hank Steuver, Washington Post, 11/27/18)

The clamor of the present, Steuver tells us, competes for attention with the intrusion of recollections of unfulfilled dreams and memories from the past, along with plans thwarted and regrets borne of hopes unrealized, any of which can be triggered by the most surprising and seemingly insignificant phenomena. Any attempts to impose order over the resulting chaos appear at first blush as an invitation to fail, when they are just manifestations of the cosmic dance between order and chaos that has gone on uninterrupted for time immemorial.

In recognition of Steuver’s “present-tense past” and by way of acknowledging the fact that this is a state of which I’m only too familiar, what better thing could I do with the material thus exposed than to explore it via the medium of writing?

***

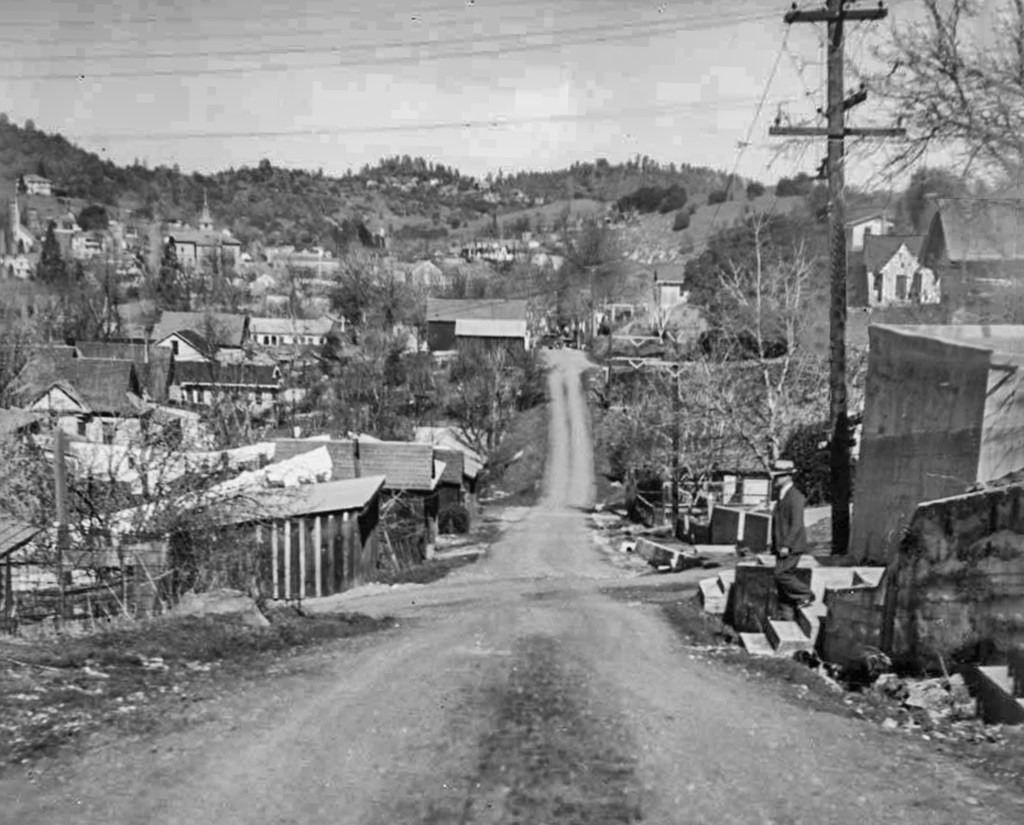

Growing Up in Sonora

Sonora in the 1950s was typical of small towns across the nation back in those days—quiet, familiar, intimate even, and far-removed from the hubbub and furor of city life in almost every way. It was a place of safety, a place where parents could allow their children to roam about, free of the fears that plague families today.

My parents would frequently send me off with a couple of dollars in my pocket to catch a meal at my favorite eatery, the Europa, followed by a double feature at one of the town’s two movie theaters. A hamburger and fries at the Europa wasn’t complete without one of Mrs. Ball’s chocolate milkshakes, brought over from the Greyhound Bus station next door. Those milkshakes still remain among the best I’ve ever encountered.

My mother and father seemed to know EVERYONE in those days. Grocery-shopping was, for my mother, as much a social excursion as an opportunity to resupply the pantry. She knew the grocer by name, as well as the butcher, the postman, the milkman, the garbageman and the guy who brought us bottled water. Most of our neighbors were friendly and personable, and some were like family.

On Saturday nights, my parents would play pinochle with the sheriff, the head of the highway department and the president of the local lumber company. The sheriff’s wife was a cashier at the Sonora Theater, one of the two movie theaters in town, the other being the Uptown Theater. ; The town’s mayor, Odillo Restano, owned the Sonora Theater, a grand, old-fashioned theater hall complete with sunken orchestra pit and balcony. It was demolished in the seventies to make way for a less artfully-inspired building dedicated to commerce, enterprise and healthy profit margins—in other words, a banking establishment.

But I digress!

As I was saying, the intimacy of small-town life provided a privileged setting for a child to grow up. Our dentist was my Uncle Charlie. Our family doctor officiated at my birth; he felt like an adjunct, if also scary, family member. In short, everything (but the doctor) felt familiar, safe, innocent, even. What unknowns lurked in the margins were still unknown to me. There were no recognizable impediments to my development save the ones I myself erected along the way.

It’s impossible to write a history of one’s place without also probing the history and nature of one’s personal contributions. And that personal element, in my case, veered as far afield as my imagination permitted—ranging from seeking any mental constructs capable of justifying self-indulgence in my younger years to, years later, “after my brains grew in,” (to quote, large animal veterinarian Baxter Black), searching for and identifying any remaining unsupportable mental constructs or beliefs in need of un-learning.

So, as is true of most things in life, what we bring to the party can have profound effects on what we experience.

Meanwhile, back to the story . . .

Three blocks south of downtown Sonora, the house I grew up in had a large yard, the street behind it being the outermost of four streets that ran parallel to each other across the breadth of the gently sloping little valley that defined the environs of my neighborhood.

Beyond the street behind my house lay an open stretch of hills, meadows and oak forest that extended for miles, relatively unobstructed by fences or buildings, toward the Sierras to our east. A rock wall, erected in the 1930s by the Works Project Administration, marked the boundary between my backyard and the world beyond. As the back street was above the level of our yard, access to it required scrambling up the wall the five or six feet to street level. Spaces between the rocks provided footholds making this climb easy for someone young and nimble to accomplish.

To be continued:

+++

Leave a comment