By

Tim Konrad

Growing up in the same house and living in it until I married and moved out afforded me a longitudinal view of how a neighborhood can change over decades.

The neighborhood in which I was raised has changed much and yet looks much the same as it did in the fifties, with a few exceptions, such as the small apartment building sitting on a corner lot once dominated by a single-family dwelling. The light illuminating the building’s parking lot now shines directly into my living room, intruding upon the serenity once afforded by the evening twilight.

That spot was previously occupied by an old wooden garage—a structure with no signs it had ever seen a paint brush save for the message scrawled across one of its doors, an artifact from WWII that stated “Kilroy Was Here.” Those three words, according to the Smithsonian magazine, “appeared almost everywhere American Soldiers went” in the years following the war, often accompanied by a cartoon-like drawing of a man with a big nose peering over a wall.

The message was so ubiquitous it was featured in a 1948 Bugs Bunny cartoon where, believing he was the first rabbit to land on the moon, Bugs failed to notice the slogan clearly displayed, carved into a rock behind him.

One day, when I was eight or nine, I chanced to lean against a wall of that structure long enough to receive a wasp sting, the experience of which is probably the reason I still recall the building these many decades later.

The other houses in the immediate vicinity remain intact save one across the street, which caught fire after the inhabitant at the time, recently widowed and on oxygen, lit a cigarette too close to her oxygen tank. She survived the fire but the house did not. The people who rebuilt had the good taste to construct a dwelling that retained the architectural spirit of the original building, which was a boon to the neighborhood.

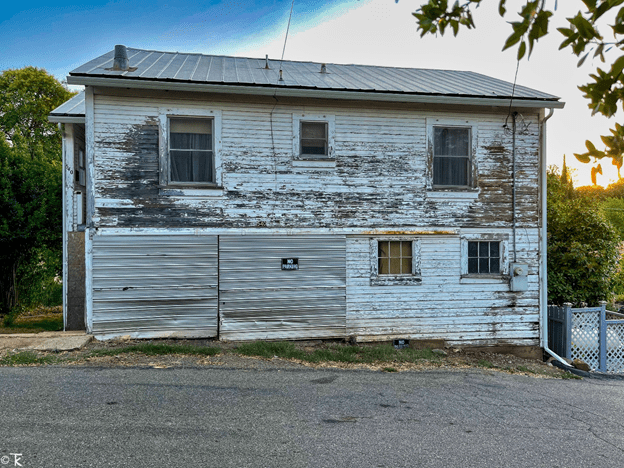

The one house in the area whose destruction would be beneficial remains undisturbed, uninhabited and unsightly, as it is literally falling down.

Situated directly opposite and across the narrow street from my parents’ house, this looming hulk can barely keep its foundation dry any more, ravaged as it’s been by time’s handiwork.

Abandoned, decrepit, fallen way past disrepair, Betha’s house awaits a purported end date that seems forever forestalled by life’s little setbacks—the glacial pace of destruction permits, a profusion of unforeseen developments plus other assorted Coyote tricks. Having outlived its purpose(s), Bertha’s house hangs around ghost-like, looming, too caught up to notice the show ended years ago.

Built right to the edge of the street on a half-lot, in a time with fewer rules, Bertha’s house has the look of an afterthought with a permanent foundation undergirding it. Two-storied, box-like and utterly devoid of aesthetic considerations, form fell prey to function before the ink had dried on its construction blueprints. The idea of setback ordinances was unknown to the Tuolumne County officials of the time, so there was nothing to prevent someone from setting foundations literally as close to street-side as possible.

Like her house, Bertha’s garden was humble but orderly, tended with the stern sort of love that doesn’t tolerate exuberance. On occasion a happy place, her yard was a child’s playground, a place to play kick-the-can on warm summer evenings as twilight faded and shadows deepened, enhancing places to hide amid the bushes.

Now overgrown and neglected, only fragments remain of the garden’s former glory—an iris here, a daffodil there—peering out from the chaos, sparking memories, real or imagined.

Grown entropic from decades hardened by remaining rudderless, left behind and abandoned in all save title, Bertha’s garden these days is left with naught to do but watch the paint continue to peel off the tortured surfaces of its old companion, the familiar hulking frame towering over it, as both house and garden slowly surrender, like their owners before them, to their ultimate fate—decrepitude and ruin!

A happy haven in its time, Bertha’s house provided shelter and nurtured a loving family, sights set on a happy future, with a son to carry on the family name. Those hopes were brought to fruition—a college graduation, a budding career, a promising marriage, children, raised in a distant enclave, followed by years spent in professional pursuits—and then retirement, those golden years now turned to dust, the hopes and dreams of three souls, united in family, now united in death. Three hearts now departed, their earthly work finished, off to explore that other place beyond toil, where joy, sorrow or surprise are no longer relevant and where expectation no longer drives the narrative.

Haunted by ghosts real or imagined, Bertha’s house today stands as a melange of memories hearkening back to a time when the world had order, a peeling paint pavilion way past its prime, a cat-haven missing its cat lady and a fire awaiting its spark.

The souls who lived there now gone, every one, Bertha’s house persists nonetheless, as if determined to maintain its prescient display of deterioration and decay as a reminder, like the graveyard, of the fate that ultimately awaits us all.

While the rest of the neighborhood structures are mostly intact, none of the original inhabitants remain, all having either moved on to other parts or other realms—mostly, due to the dictates of time, the latter.

To be continued:

+++

Leave a comment