A collection of short essays on my recollections of growing up in the Sierra foothills in the 1950s.

Recollections of my maternal grandmother

Part II

My grandmother lived in San Mateo and my parents and I would make the long journey down from the hills and across the Central Valley to see her every 6 weeks or so. The trip took longer back then. There were no divided highways at all until we reached Alameda County, and the road went straight through downtown Manteca and Tracy, which slowed things even more. Crossing the San Mateo Bay Bridge, you could always tell when you were nearing San Mateo by the scent of the noxious perfume produced by the mixture of salt water with the city’s sewage as it was released into the bay.

When I was a young child, my parents would sometimes leave me with my grandmother for a week during summer vacation. My grandma wouldn’t let me play outside with the other kids in the neighborhood, but she never offered any explanation other than to say that it would only lead to trouble.

This didn’t sit well with who I fancied myself to be as a child, or, for that matter, at just about any other point in my life. In response, I went out and played with a neighbor boy a couple of times in defiance of her orders. Each time I did so, she would scold me fiercely afterward.

***

Once I remember going to a drive-in movie with my grandma and one of her women friends who lived across the street and down a few doors from her house.

The woman, Mrs. Hultberg—my grandma and her friends always addressed each other formally—sat in the passenger seat of my grandma’s classic old 1939 Ford coupe. My grandma sat behind the wheel, with me perched in the back seat watching the movie over their shoulders.

The flick was a jungle thriller, shot in black and white, featuring European explorers in Pith helmets traversing the jungles in search of a gold cache allegedly buried in a “lost city” somewhere in Brazil’s Amazonia.

Actors portraying jungle explorers always wore those strange-looking head-toppings in the movies back then. No respectable jungle romp was without them.

Looking back on it, the whole thing seemed quite surreal—me sitting in a really cool old car perched between two old women watching people being ravaged by fierce savages or stripped clean of their flesh by roiling schools of bloodthirsty piranhas.

***

I tried several times in my teen years to buy that car from my grandma. She hardly ever used it at that point, and had rejected several offers from eager young auto enthusiasts interested in purchasing it, yet she showed no interest in entertaining my offers.

***

Another recollection I have concerning my grandma was the time we sat together in my parents’ Oldsmobile in a parking lot at the Hillsdale Mall in San Mateo while they shopped for Christmas presents.

I was older by then, perhaps 12, and remember being fascinated by my grandmother’s recounting of her experiences in Utah during the great influenza epidemic of 1918, the pandemic that took her husband, my grandfather Bert’s life.

My grandma explained how, early in the ordeal, my grandfather and mother and her brother Jack had come down with the virus and how their entire household had been subsequently quarantined for the duration of the epidemic.

In the beginning, friends would come by to see them, wearing masks while standing outside and visiting through an open window, sometimes bringing food to share.

As the epidemic wore on, my grandmother said, fewer and fewer of their friends appeared at the window, until finally, hardly anyone showed up.

Afterward, they learned that many of their friends had perished, along with one quarter of their town’s population.

***

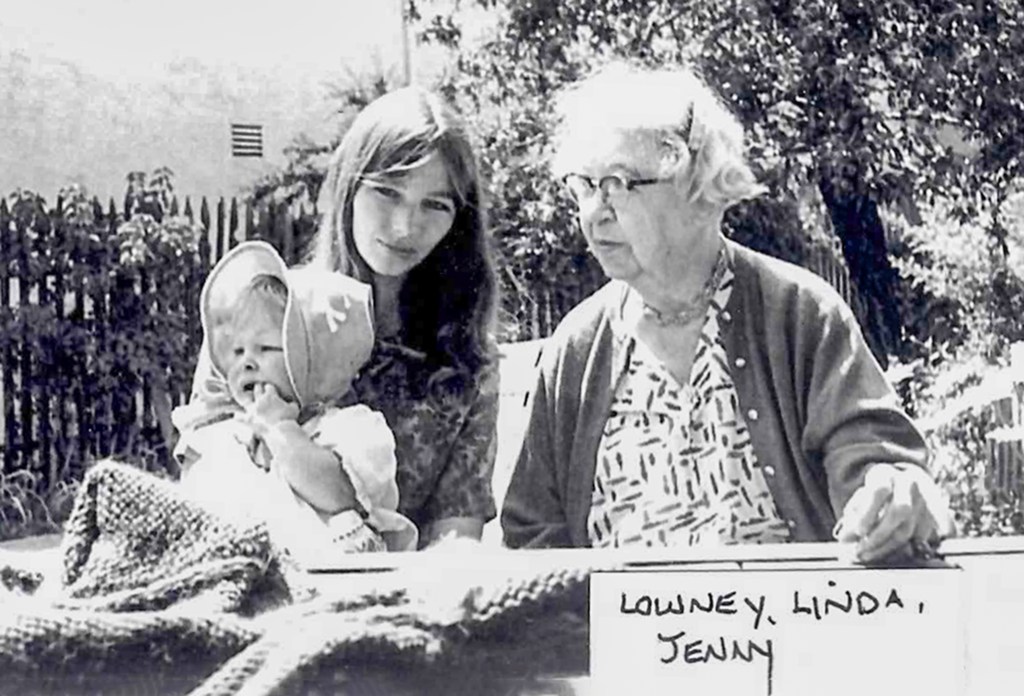

My cousin Linda, a couple of years my senior, had much more complete recollections of my grandma than I did. Accordingly, I have included an essay about her that Linda penned as a writing assignment when she was attending San Francisco State College in the early 60s. I particularly like the imagery Linda created with her detailed recounting of our grandma’s appearance and personality!

“My grandmother lived in an old brown shingled house in a quiet part of town, with pepper trees shading the sidewalk in front.

She was a large woman who, as far back as I can remember, used a brown wooden cane to aid her walking.

She always seemed ashamed of the cane and the limp in her leg which was the result of a broken hip when she was quite young.

She was Danish and used orange food coloring to dye her white hair. It was flame-red, but she insisted that she had natural colored auburn hair.

She always wore at least two dresses, one on top of the other, a flowered hem trailing underneath.

She wore two pairs of thick stockings on her legs, rolled at the knees like sausages.

I loved to watch her prepare to ‘go out gallivanting.’

One dress of black silk sprigged with white flowers beneath a yellow checkered crepe with gold buttons down the front.

Then the two pairs of stockings and then her jewelry.

There was always a huge brooch at her bosom and strands of beads around her neck, one on top of the other, green shiny beads, gold chains, strings of ceramic flowers.

She would let me pick out her rings for the day. One for each finger. And her earrings.

I can never recall a time that she walked out her front door without her large green straw hat on, the elastic band (tucked) under her chin.

She would periodically replace the drooping silk flowers around the band, but it was always the same hat.

She would rouge her cheeks slightly and then her attic room would fill with powder as she patted her face in a flurry of pink dust.

She smelled like violets.

And with a patent leather bag on her arm and the wooden cane over the other, we would leave the house to begin our excursions.

She drove a green 1939 Chevy coupe with a running board and a stick shift with a round shiny knob on top that had a rose inside it.

The dash board had a rubber spider glued to it and it shivered when the car started.

After a lot of noise and smoke we would back slowly out of the driveway and go bravely at her full speed of fifteen miles an hour down the avenue.

She would entertain me by stopping at every pet shop we saw.

We would wander around, playing with the animals, asking their names and what they ate as if we intended to buy one and then leave.

Often, we went to the animal shelter on the pretext of looking for a dog or a cat and go on a tour of the shelter. This is how we would fill our afternoons together.

Then she would take me home for dinner.

We would eat onion and garlic sandwiches or fried scones with jelly.

She never went anywhere without a bag of white flat mints and her kitchen cupboard had tins full of them.

I was allowed to eat anything I wanted whenever I wished.

She had an old and very out of tune piano in the dining room. Sometimes I would play for her and she would smile and tap her cane and fall asleep.

In the evenings she would turn on the lamp and the gas heater and we would sit at the table playing Chinese marbles. She could play the game for hours without tiring.

She preferred to keep me indoors with her. The neighborhood children were ‘mean little hoodlums.’

I rarely went out front but could go in her backyard and play with her cats.

I would sit on a marble bench surrounded by weeds taller than my head and watch a spider spinning between the fig tree and cactus while the clothesline squeaked as my grandmother hung the laundry.

She had two lady friends, both of whom she had known for years. Until the day my grandmother died, they addressed each other as Mrs. Hultberg, Mrs. Clayton and Mrs. Wolfe.

They were always very formal and never used first names.

They would come and visit whenever I was staying there.

I was usually the topic of conversation.

I would sit fidgeting on the sofa staring out the front screen door at the kids skating down the sidewalk while my grandmother poured coffee and referred to me as the ‘poor dear.’

Her favorite expression was ‘oh, murder.’

The ladies loved to discuss the horror of the world and the bloodshed that was going on and ‘oh, what would it all come to?’

And then they would warn me of the dangers of being on the streets alone and never to speak to men.

The living room of her house was dark and faded.

It had a long deep sofa and hand-made lace doilies on the arm rests.

She had yellowed lace curtains gathering shadows and dust in the windows.

My bed rolled straight out of the wall, which always amazed me.

It did not pull from the wall or fold down, it rolled straight out of the wall leaving a dark black tunnel at its foot.

I always supposed the cavern to be full of spiders and mice.

My uncle had built the bed into the wall. The wall was one large shelf with cupboards and drawers and below that were two handles that pulled out my huge double bed.

When I was very young, my grandmother would plug in a lantern on the shelf above my bed before I went to sleep.

It was a cylinder lantern that had a forest fire scene on it. Deer were running through the trees.

It turned around and appeared to be alive. I would lay and watch the flames until I fell asleep.

My grandmother would give me strict instructions not to answer the front door before she said goodnight, which always left my imagination running wild.

Who would be on the other side of the door, late at night?

Then she would go up to her attic room and read detective stories and pulp murder magazines until late into the night.

The next morning, she would tell me of all the horrible nightmares she had and wonder if it was the onions we ate that gave her such ‘bloody dreams.’

Her room was full of murder magazines. In every corner and along the walls were stacks of the blood-curdling stories.

I was not allowed to look at them. They might scare me.

She refused to be called ‘grandmother.’ She was afraid it would age her.

I called her by her first name, ‘Lowney.’

She had been born in Logan, Utah and worked in her father’s dry good store until she married her first husband, Bert, my grandfather.

After five years of marriage and two children, Bert died of the flu, leaving Lowney with two children and no means of support.

She journeyed out to California to look for work and settled herself and her children in San Mateo.

It was there that she met her second husband, Ernest Wolf. He ran the Yellow Cab Company in San Mateo.

They were married and had a son a few years later.

But Lowney’s temper was like fire and her moods extreme.

Ernest was a spender and a drinker.

She divorced him and for the rest of her life, sat inside her house in San Mateo with her cats and her youngest son.

He spent most of his time at work. Thus, whenever I came to visit her, it was really an occasion as she didn’t have that much company.

We both loved to fight and had the same flare for drama.

We would sit for hours, she a woman of sixty or so, myself just nine or ten, and gossip about the problems of the world, the horror of it, and when we tired of that subject, we would begin on our family.

She was an excellent cartoonist and would sometimes occupy her time by drawing with India ink clever cartoon sketches of her friends and circulate them with her correspondence.

Every letter I received from her was full of pages of drawings.

She might have made a living of her art, but for her lack of ambition or confidence.

She preferred living quietly though lonely and protected her privacy with a fierceness.

As she aged, she began to limp more and became quite heavy but still had her love of jewelry and hats, colored calico dresses and rouge.

She never gave in to senility. Her stubborn humor remained the same.

She became ill in her late seventies but refused to stay in the hospital, shaking her fist at the nurses and cursing at every doctor who touched her.

She knew she was going to die, and being rather tired of life, I think she welcomed it.

She wanted to come home and so we brought her home to convalesce. It was in her own bed that she died, and that was of her own choice.

I visited her once during this period of sickness and brought my year-old child with me.

I placed her great-grandchild in her arms, across the blankets.

She recognized us both, reached under her pillow, pulled out a wrinkled waxed bag of mints and, after putting one in her mouth, placed the bag in my baby’s hands.

I had to laugh. We both did.”

To be continued:

Leave a comment